Water rich or water poor? A quantitative tool can help water resources planners

March 02, 2018

March 02, 2018

Using quantitative water balance models can help city and state planners understand the availability of water resources—now and in the future

The phrase “water, water, everywhere…” may resonate with you—if, like me, you call Minnesota your home. It’s the “Land of 10,000 Lakes.” In this region, we are lucky to have adequate freshwater supplies to meet our population’s needs. The state has highly productive aquifers that are heavily relied on by municipalities in the Twin Cities metropolitan area and there are large surface water bodies that we are also able use.

This is an entirely different hydrologic context to what I experienced growing up in California. California has always faced water management challenges and will continue to do so. Though California has a Mediterranean climate with a well-defined dry season, it is a climate intrinsically of extremes. The state has dealt with seasonal and multi-year droughts, and the duration and severity of these multi-year droughts will likely increase in coming years. In addition to droughts that have plagued California, the majority of precipitation falls in the northern part of the state, but the majority of water is used in the southern part of the state. Therefore, California has an extremely complex network of conveyance and storage infrastructure to transport water throughout the state.

Water is an inherently complex resource to manage—it is often not available when and where we need it.

In 2013, while working for the Stockholm Environment Institute (developers of WEAP, Water Evaluation and Planning software), I began work on a project with Stantec where I learned more about California hydrology and the complex operations that accompany water conveyance throughout the state. Using the WEAP software, I worked on a team to develop the Sacramento Water Allocation Model (SacWAM) for the State Water Resources Control Board (State Water Board) in California. The State Water Board is the state agency in California that governs water rights, determines water quality standards, and regulates wastewater and stormwater discharges throughout the state. The WEAP software embeds a hydrologic model within a system operations model. The model estimates stream flows throughout the Sacramento Valley, one of the largest and most productive agricultural regions in the United States.

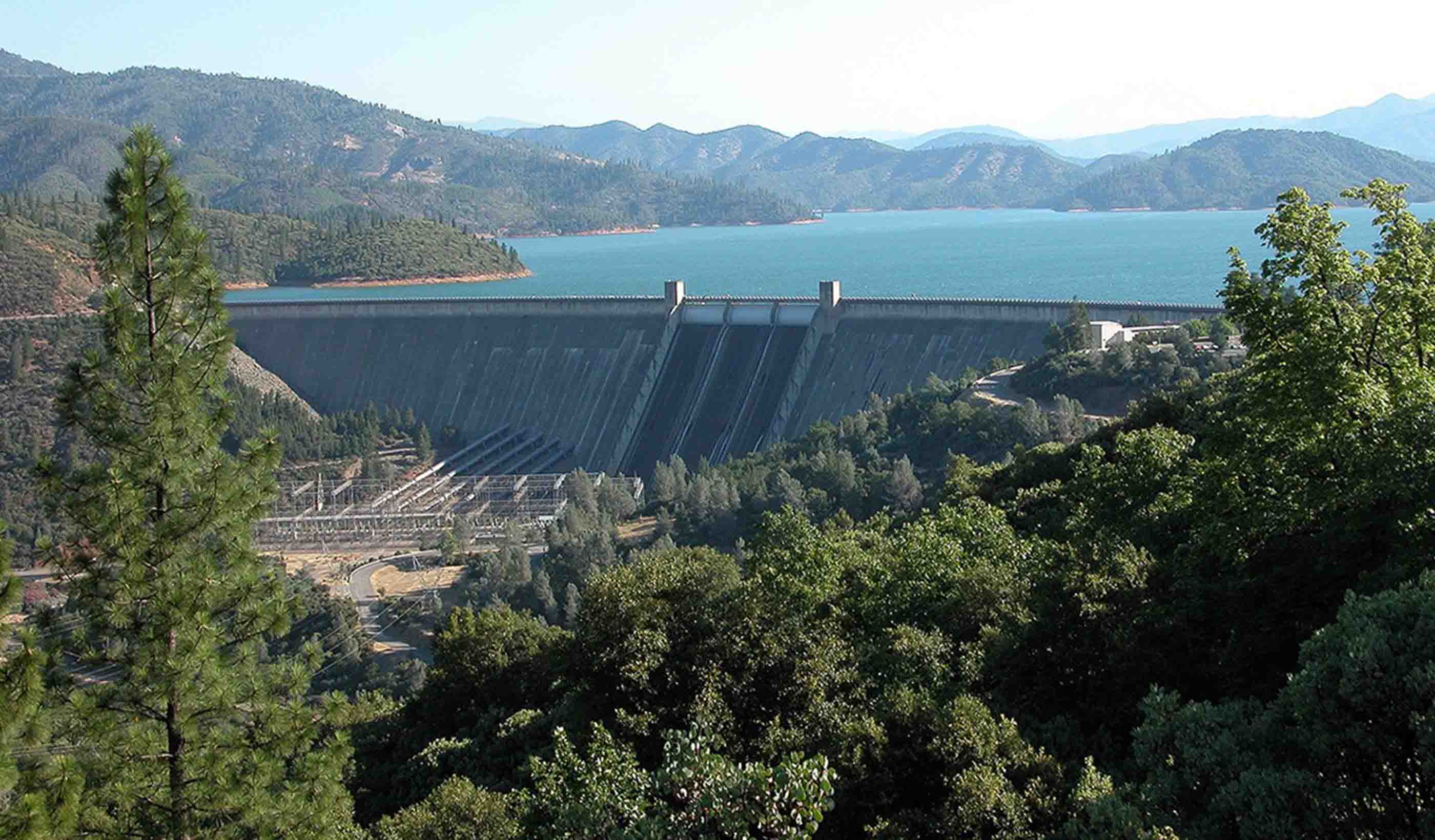

Lake Shasta on the Sacramento River provides water supply for large urban and agricultural centers in California. It was modeled in the Sacramento Valley WEAP program to understand water supply reliability.

Understanding baseline water availability throughout the Sacramento Valley region allows decision-makers to better allocate surface and groundwater resources, and understand future and alternative management scenarios.

For example, SacWAM can be used to estimate the monthly flow regime in a river, or typical storage levels in a lake or reservoir, and it can also be used to simulate future flows in that same surface water body, under various regulatory or climatic scenarios. For instance, our reliance on a certain water body could be sustainable under existing conditions, but if we were to increase the population that relies on that supply source by 20 percent in the next 30 years, what would that then mean for surface water levels? The WEAP software allows us to inform crucial water management questions that will face future generations.

Water management in California is certainly different, given its unique geography, climate, and artificial conveyance system.

The types of questions that are being asked in California will inherently be different from other states. That doesn’t mean that there is no role for quantitative tools to be used by planning agencies, cities, and states in the often water-rich Midwest. For example, despite an apparent abundance of freshwater resources in Minnesota, water-supply issues do exist and will likely become more prevalent with population growth in urban centers.

WEAP modeling platform (developed by the Stockholm Environment Institute) is used to understand water users and their water supplies. This figure shows the extent of the watersheds that were analyzed in the Sacramento Valley.

A great example is the historic water resources lawsuit surrounding groundwater appropriation in the Twin Cities related to White Bear Lake in Washington County, Minnesota. Plaintiffs claimed that groundwater used for public water supply in this area was over-appropriated and that a protective lake water elevation for White Bear Lake should be set. This single issue is not an isolated case-study. Already, issues are popping up across Minnesota related to groundwater use and stormwater quality for irrigation—issues that highlight the critical need to understand the intricate relationships water has throughout its lifecycle.

Water is an inherently complex resource to manage—it is often not available when and where we need it, and there are many stakeholders with a variety of needs that must be met. This is likely not the only water resources management decision that Minnesota will face in the next few decades. Long-range planning is crucial to understanding the temporal and spatial availability throughout the Twin Cities metropolitan area.

Are we currently using quantitative tools to understand water resources availability? Do we understand what future availability may be, given factors such as climate change and population growth? Quantitative water balance models like WEAP can help us to make informed management decisions.