Mapping your culture: How to help communities identify their heritage landmarks online

May 05, 2022

May 05, 2022

Thinking of moving community cultural meetings from in-person to online? Read some lessons learned from a recent project in North Simcoe, Ontario.

Tell me a story. Show me a landmark. Introduce me to your history.

As a senior cultural heritage specialist, I love learning about a community’s background, visiting culturally significant sites, and helping people identify their cultural assets.

I’ve worked on several rewarding projects that have given me the chance to collaborate with local groups to map out heritage sites. During these projects, my team typically arranges community cultural meetings where we meet residents, provide coffee and cookies, unfurl paper maps, and create spaces where people can talk, learn, and share ideas.

For a recent project, however, public health guidelines due to COVID-19 led us to pivot our outreach strategy. We created a digital tool and performed outreach virtually. If you’re considering switching your community cultural meetings from in-person to digital, I’m happy to share some insights from my experience.

The Culture Alliance consists of Beausoleil First Nation, The Town of Midland, The Town of Penetanguishene (pictured), The Township of Tiny, and the Township of Tay.

Before I dive into my advice, I’d like to tell you about a recent project that has helped to identify heritage and cultural asset sites in the North Simcoe area of Ontario, Canada. We worked with the Culture Alliance in the Heart of Georgian Bay—a joint culture committee of five Ontario communities—to weave its stories through identifying cultural assets like landmarks, cemeteries, plaques, museums, and public art with a unique digital platform.

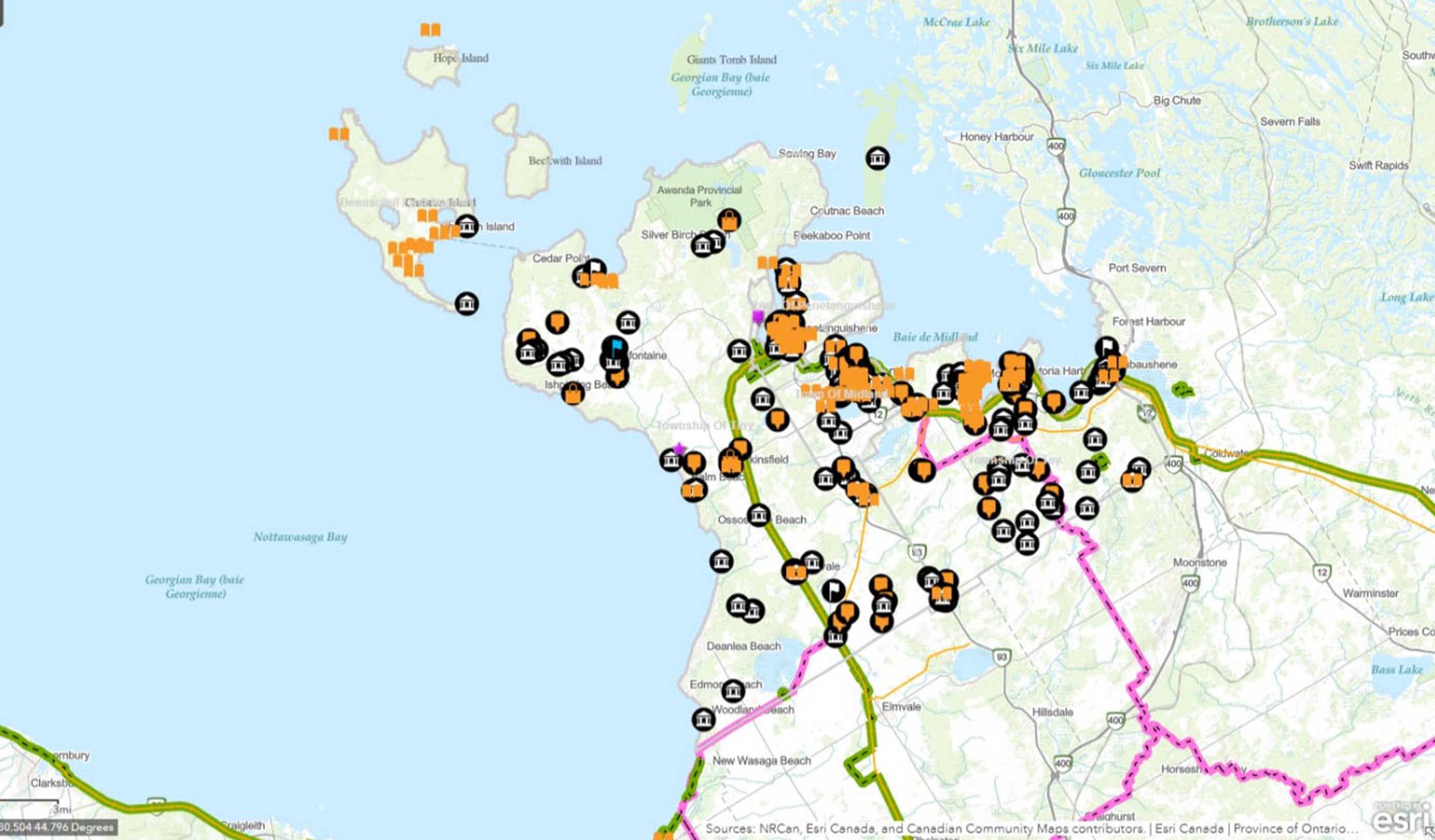

The project, known as Let’s weave our story - Tissons nos cultures - Ambe kidaa aakzokaanan, provides residents with an online map to identify locations indicating sites of interest. I’ve read dozens of entries that highlight the area’s rich cultural heritage: Murals that celebrate the area’s history, homes of prominent business leaders from the 1900s, statues along the waterfront, and information about churches, cemeteries, and barns built in the 1800s.

Aside from building a feeling of community, these sorts of tools can provide data that can be used for tourism, business promotion, and leveraging funding for community planning purposes. It’s so important to generate that excitement and momentum around this valuable data. Knowing what’s out there can form the basis for a range of outcomes from cultural masterplans to climate action plans.

The Culture Alliance consists of Beausoleil First Nation, The Town of Midland, The Town of Penetanguishene, The Township of Tiny, and the Township of Tay. Our team hosted online discussions in each of the five communities that also included demonstrations on how to use the tool to mark cultural assets on the map. This data represents a starting point for the Culture Alliance as it builds awareness of the rich cultural heritage in the area and helps conserve the recognized heritage value of the local community.

If you’re considering a similar cultural mapping project and contemplating using a digital platform, here are some important points to keep in mind.

Here’s a screenshot of the digital map that community members used to identify cultural assets.

First thing first: Identify your key stakeholders. Those stakeholders would likely be heritage committees, arts organizations, historical societies, tourism staff, and other similar groups. Reach out to them early and build momentum for the project. If you neglect this step, you risk ruining the community buy-in and alienating your key audience. You may end up with a tool that doesn’t work for everyone.

If you’re building an online platform, it’s important to ensure that everyone involved feels like they’re on the same page on a technological level. Is your tool technologically feasible? Can it fit into a system that’s already running?

For our Culture Alliance project, we spoke directly to the geographic information system (GIS) staff at the various communities to make sure we could integrate our project into the technology they were using. Our team, connected with GIS staff to make sure they could receive data in the right format. In this case, in my role as project manager, I almost needed to get out of the way and let the tech experts speak to the other tech experts.

These types of projects can provide the foundation for an incredible amount of information sharing and collaboration.

If you’re hoping to encourage a lot of community involvement, it’s best to keep your digital platform user-friendly. Build something, and then be willing to simplify it. Don’t potentially turn off your users by trying to use a complicated platform. Keep your audience in mind and realize that not everyone might be as computer-savvy as you are.

For the Culture Alliance project, we did a soft launch. This helped us figure out a few bugs and make tweaks. We continued to listen to the community and shifted things where it made sense.

A statue by the waterfront in Penetanguishene, Ontario, that shows the meeting of France’s Samuel de Champlain and Chief Aenons of the Wendat Bear Tribe in 1615.

A project charter that clearly states the objectives and meaning behind your project can be very helpful as well. When a question pops up about an approach to take, you can revisit your project charter and see if the decision aligns with what you’re trying to accomplish.

For our project in North Simcoe, we established a project charter early on with the Culture Alliance, and we continued to reference that charter. The idea of community-building became a big focus of the charter, so we knew that our online map—and our virtual information sessions—needed to reflect that community celebration component.

It’s a wonderful feeling when your database goes live and residents can start adding new locations on the go. It’s wise to set up a vetting process, so submissions can be reviewed and approved before becoming publicly visible. Some members of your community may have differing views on historical events—and from an academic perspective, there are many nuances when it comes to accurate representation of history—so it makes sense to set up a framework for quality control. Use the project charter to guide you when setting up a vetting process.

In addition, you may want to ask contributors to provide an email address to add a layer of accountability to the process and give you the chance to confirm details of identified assets. Make sure that the contact information remains confidential.

A ship with a rich history can be considered a cultural heritage asset. Pictured: A 124-foot replica of the warship H.M.S. Tecumseth in Penetanguishene, Ontario.

These types of projects can provide the foundation for an incredible amount of information sharing and collaboration. When speaking with residents, I emphasize that we’re relying on their input. Because without the community, culture mapping tools wouldn’t work nearly as well.

I’m thrilled that we helped the Culture Alliance and its five Ontario communities identify their diverse heritage resources, and I hope you’ve learned a bit about what it takes to transition your community cultural meetings from in-person to digital. The project has succeeded in highlighting and strengthening the cultural bonds between the five communities, creating a communal space where cultural assets are recognized and shared. I can’t wait to work on another project like this one.

So, tell me the story of your community. I’d love to hear it.